In Part I of this two-part series, we looked at the life of the visionary who is Serge Lutens, a lonely man, born in war, unwanted by many in his family from the time of his birth, whose very existence was considered to be “a problem,” but who went on to revolutionize the worlds of fashion, beauty, photography, and perfumery. Now, in Part II, we’ll talk about his philosophy and approach to perfumery, as well as the sources of his inspiration. We’ll address the issue of inaccessibility and exclusivity, and his views on such issues as whether perfumes are aphrodisiacs, what he thinks about fragrances being unisex, and how his creations are ultimately about the search for identity. (You can also turn to my exclusive interview with Serge Lutens himself if you are interested in learning more about the man.)

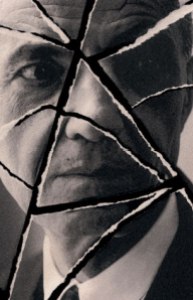

Photo: Marco Guerra, taken at Serge Lutens’ Marrakesh villa. http://marcoguerrastudio.com/?projects=portraits

SERGE LUTENS & PERFUMERY:

Like every artist, Serge Lutens reveals a little about himself in each of his creations. For example, Tubereuse Criminelle shows his love for Baudelaire (who is my favorite poet as well), while De Profundis reveals, depending on your interpretation, either a spiritual appreciation for the Psalms or his enjoyment of Oscar Wilde. Yet, Serge Lutens’ intellectualism is clearly drawn to the darker things in life. Baudelaire, after all, is known for Les Fleurs du Mal, a compilation of poems about death, sex, decay, hedonistic excess, and finding beauty in the darker parts of human existence.

De Profundis is an extension of the same theme, finding beauty in death. In a telling bit of symbolism that would have Freud salivating, Serge Lutens’ strange backstory for the fragrance includes the line: “Clearly, Death is a Woman.” Oh dear. The rest of the story, as provided by Fragrantica, isn’t any cheerier:

When death steals into our midst, its breath flutters through the black crepe of mourning, nips at funeral wreaths and crucifixes, and ripples through the gladiola, chrysanthemums and dahlias.

If they end up in garlands in the Holy Land or the Galapagos Islands or on flower floats at the Annual Nice Carnival, so much the better!

What if the hearse were taking the deceased, surrounded by abundant flourish, to a final resting place in France, and leading altar boys, priest, undertaker, beadle and gravediggers to some sort of celebration where they could indulge gleefully in vice? Now that would be divine!In French, the words beauty, war, religion, fear, life and death are all feminine, while challenge, combat, art, love, courage, suicide and vertigo remain within the realm of the masculine.

Clearly, Death is a Woman. Her absence imposes a strange state of widowhood. Yet beauty cannot reach fulfilment without crime.

Hard as it may be to believe, De Profundis’ backstory is (in my opinion) almost joyful, relatively speaking, as compared to that of La Fille de Berlin. Contrary to some people’s belief, that fragrance has nothing to do with Marlene Dietrich or the decadent excesses of Weimar Germany. When I was writing my review right before Valentine’s Day, and during my research, I stumbled upon a YouTube video in which Serge Lutens read the story behind the fragrance. I also found a brief interview he gave to the New York Times. The two things made abundantly clear that La Fille de Berlin was focused on the struggles of a German woman or women in Soviet-occupied, post-war Berlin. It is a story that is filled with implications of rape and, even, perhaps murder, to the point that I can’t really bear the perfume itself, even to this day.

At the time, I couldn’t help but wonder, “Who is this man?!” Baudelaire, Oscar Wilde, the bleak backstory about the beauty of Death for De Profundis, and now, rape by Soviet occupiers, the transformation “of murder into a masterpiece,” and a woman’s lips covered by “the blood of Siegfried”?

Now, however, with all the things which I have learnt and which are discussed in Part I of this series, now, I get it. It’s about survival through the very worst of human suffering, through the greatest of all pain, even through the most traumatic aspects of war. It’s about the triumph of survival. And, ultimately, it’s about his triumph, and that of his mother (with her own wartime experiences) as well.

This ability to take the wounds of the past and see them as something more positive is reflected in his comments to The Independent in the interview discussed in Part I:

In one breath Lutens states, “You have to create your own happiness, we are the key to our own happiness,” while in the next he says, “It’s very dangerous to believe in such a cliché”. What he means, of course, is that happiness should not be confused with material wealth, beauty or success. “Even if society thinks you’re a mistake, you need to come to terms with it,” he says without sadness. “Maybe be happy about it, rejoice. Sing it as a song, clothe it, perfume it and close it to yourself.”

Serge Lutens has certainly clothed his past in perfume, and used it as a source of happiness. Yet, you may be surprised to learn that he does not actually see himself as a perfumer at all. According to the FAQ section of his website, he sees himself merely as a storyteller whose fairytales or fables are expressed through flowers and wood.

It is a process that takes time, and one whose inspiration often lies at the junction of “scent and memory.” He elaborated on both issues for The Independent:

“Sometimes it takes 12-17 years [to create a new perfume],” he says. “Sometimes it takes one year – that is the minimum – and then I will say that’s it. Then I’m not interested any more, I’ve said what I had to say.”

Although the inspiration for each creation comes from a different source, Lutens believes that through his work he is “trying to determine an identity, find a new language”. He shares his philosophy of scent and memory that underpins all his work: “It is an exercise of the memory, of your sensitivity. By the time you turn seven, this is what we call in French the reasonable age, you are going to, so to speak, record 750,000 odours in a box. Your nose is not made by these fragrances, but is there to assess whether you like, or you love, or you hate. These odours are going to create an interlace of paths going in all directions. From these odours you’re going to smell millions more, and only say ‘I love’ when you recognise something, not discover something. What you can recognise is nothing else but yourself. So around this [identity] I am trying to make the perfume recognisable. If I am using wood I want the perfume to smell like wood.”

Indeed, wood marks the beginning of Lutens’ fragrance journey. In the past he has attributed his first trip to Marrakech in 1968 as his moment of epiphany. At a small wood-workers’ studio in the souk he found a piece of cedar, “a quite attractive and a captivating type of wood; tasty, very sweet but also musky”. So overwhelmed was he by the scent that Lutens knew he had to make a perfume from it.

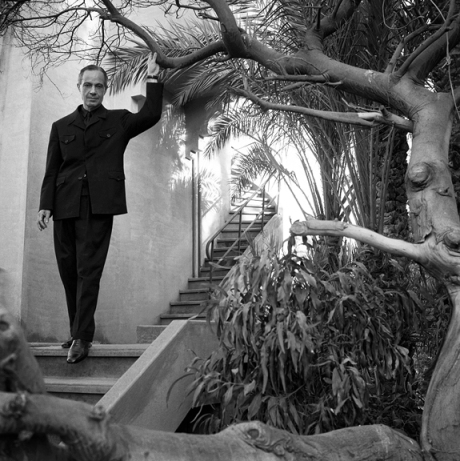

The impact of Morocco on Lutens went far beyond the mere appreciation for cedar. The country, its history, and its culture have become the source of much of his perfume inspiration. A good chunk of the Lutens line is oriental, after all, with clear references to the Middle East. Yet, Morocco has also become something more. It’s become this very solitary, lonely man’s sanctuary, his peaceful haven, and the place where he purposefully goes into self-imposed exile for much of the year. In my research into Lutens’ life, I stumbled upon a detailed photo series of his stunning, elaborate villa in Marrakesh, and, honestly, if it were my home, I’d probably never leave either!

The site, Kontraplan, features a photo-series called Casbah Confidential that shows Serge Lutens’ hideaway. I was so completely staggered by the sight of various rooms, I decided to include a few of them below. In order to give full credit to the site, all photos have the Kontraplan link embedded within, so clicking on them will take you to their article:

It’s quite something, isn’t it? Can you blame me for straying from the issue of perfumery? And can you imagine living in such Oriental opulence?! (On a side note, I wouldn’t be surprised if that militaristic room played some inspirational role in his development of either Sarrasins or Cuir Mauresque!) But we should return to the topic of actual perfumery.

In the FAQ section of his website, Serge Lutens shares a few of his thoughts on everything from the question of whether perfume can be an aphrodisiac, the issue of “unisex” in perfumery, and the purpose of fragrance. Please accept my apologies in advance for the wonkiness in the formatting, as the Lutens code and WordPress’ system seemed to be at war for much of the time. (And HTML coding is not my thing!)

- What is your current philosophy with regard to perfume?

- Perfume resides at the very heart of us. It is a means of self-expression. It is the dot on our “I”, a way of contemplating ourselves and sensing who we really are. It is also, in some ways, a weapon which seduces more by consequence than design. Perfume exists in the first person.

- Do you think that perfume can have an aphrodisiac effect on the people around us? What makes a perfume seductive?

- To be precise, there’s no such thing as an aphrodisiac perfume only aphrodisiac people. Wearing perfume doesn’t make you seductive. Being seductive is the result of being alive; being loved for who we are is what is important and not trying to be someone else!

- What is your opinion of unisex perfumes?

- Ask the perfume what sex it is. Who knows if an oak is male or female, or whether a rose is a he or a she? A watch is made for telling the time, isn’t it? It doesn’t matter whether it’s large or small, so long as you can read the face clearly so that you’re on time for a date! Are there CDs for men and CDs for women?! Absurd! Perfume is a product aimed at the senses not a particular gender.

- What are your favourite perfumes? Are they the most successful ones?

- The only favourite I have is the one I’m working on at any given time. It’s impossible to choose. Some of them marked the start of a new period, such as Féminité du bois which introduced the theme of “identity”, or Ambre sultan, which was the point of departure for my Arab period. Those two perfumes obviously made an impact but, as far as I’m concerned, they’re just as important in this respect as Serge noire or De profundis. They create short circuits and express emotions through fragrance. They serve as reference points or “repères” in French (notice how that word contains the word “père” or father). What interests me is going further, not into the perfume, but deeper into myself, exploring my innermost depths to extract darkness from light, and make it just as visible. [Emphasis added.]

- What perfumes do you hate? What ones do you wear and why?

If I hate a perfume, it is only because of the person wearing it, whom I either can’t stand or who makes me feel that we inhabit different worlds and that it would be impossible for us to find any common ground! I could love the most ordinary or revolting perfume if it were worn by someone I found attractive! Personally, I rarely wear perfume and, when I do – and I do so advisedly – I wear Cuir mauresque, applied liberally so you can tell what I’m wearing. I go for this one as much because of its name as because of its fragrance, which is a leathery scent, like Cordoba leather tanned over acacia. [Emphasis added.]

As a side note, I recall reading somewhere that his choice of perfume is not Cuir Mauresque, but Serge Noire. It is one of the more challenging perfumes from his export line, in my opinion, and a fragrance that reportedly took ten years to create. I can see the fragrance suiting him because, for me, Serge Noire is the story of a phoenix with a two-sided, almost Janus-like duality. And, as this peek into his history may show, Serge Lutens is definitely a phoenix in some ways. Still, if he wears Cuir Mauresque, I’m even more glad as it is one of my absolute favorite fragrances from his line. It is a scent that I think oozes classic sex appeal, a fragrance that would suit Ava Gardner, just as much as the man who began his career by celebrating female beauty at places like Vogue and Dior.

The contradiction in his personal perfume choices matches the contradiction within the man himself. The interview in The Independent emphasizes more than a few times that Lutens can be, as they put it, “contrary”:

On the one hand, he talks dispassionately, almost disparagingly, about people who declare their work a passion, but then declares that if he did not create he would die. To him, the message is important, the medium only secondary: “The passion of fragrance does not exist. You go inside something, you’re pulled to something you can’t resist despite yourself. But that’s not a passion for a fragrance; it would be ridiculous to call it that.”

Or take his view that perfume should be “inaccessible.” It is a philosophy that Lutens seems to have intentionally tried to render concrete in the most literal, geographic, physical sense possible: you can’t get to his Salons directly from the street, but, instead, you have to enter from the gardens of the Palais Royal. The Independent article has more on the issue of inaccessibility, the concomitant aspect of exclusivity, and the paradoxes within Lutens’ view:

[His store’s] inaccessible location was apparently chosen by Lutens to “attract a clientele of connoisseurs, not casual customers”. […][¶]

Originally sold only through the Palais du Royal, his creations are now slightly more widely available, with selected stockists including specialist perfumery Les Senteurs and Harvey Nichols. The complexity of the blends, the narrative behind each scent and the formulation of cosmetic means that this is a brand that appeals to aesthetes. “Perfume is just molecules,” he says in his contradictory way. “The best perfume-maker was the wind, rivers and pollens…”

Lutens does not believe perfume should be accessible, nor that it should be worn every day. To him, if you wear perfume, “you are giving yourself arms, weapons. Transforming a weakness into a strength, protecting yourself by making a stand. This is the main purpose of my perfumes – strengthening your inner self”. Indeed, he explains that he only wears his own fragrance of choice, Cuir Mauresque, very rarely: “I wear it because it makes me feel good on this particular day”.

His philosophy of “perfume as weaponry” differs vastly from my own views of the purpose or nature of perfumery, but I’m fascinated by the psychological layers behind it. And, ultimately, I’m even more fascinated than I originally was by the man himself.

In the past, I set out to systematically answer the question — “Who is this man?!” — by exploring the side of “Uncle Serge” that he’s shown in his olfactory creations. This new journey into his biographical past has been a further attempt to understand the man whom I admire and respect like few others in the perfume world. Nonetheless, I always knew one could determine only the tip of the iceberg, and little else, from second-hand accounts. Even so, this journey has left me simultaneously more perplexed, more awed, more confused, more illuminated, more impressed, and more at a loss of what to make of Monsieur Lutens than I was before.

Perhaps that is how it should be. Genius is complicated. Visionaries can be contradictory, and their core essence sometimes elusive. Serge Lutens is a quiet, complex, unbelievably talented, utterly brilliant man with a painful past, a vast range of interests, an enormously inquisitive intellectual mind, and a unique creative vision. One can’t neatly tie up such a man in a well-ordered package, and stick a bow on him. If his perfumes show anything, it is an infinite capacity for metamorphosis, and more layers than an onion. In that, and in their sophisticated, multi-faceted, sometimes difficult, contrary nature, they are the ultimate representation of the man behind their invention.

So, perhaps the best one can do in trying to decipher the enigma that is Serge Lutens is to remember that his olfactory art is really a search for identity, an identity he himself does not always understand:

“I don’t know what I am really, but by creating my own weapons and talking about them I provide them to you. Some people are going to recognise my fears. I do not want to be recognised or famous, I don’t really care about having my name in big letters, the point is to recognise who you are. All I’m talking about is identity – that is all I’ve been talking about my whole life.”

[UPDATE: you can read my exclusive interview with Serge Lutens here in which he talks more about his intellectual interests, his artistic loves, his philosophy, and his aesthetic approach to perfumery.]